From time to time some of us start wondering about simple questions such as: ‘What is the direction of a valley?‘ The direction of a river is easier to determine, since it flows a certain way. But the valley? It turns out that the early Norwegians set the direction of a valley as the natural way to enter it. As the glaciers retreated after the last ice age and Norway reappeared, the land (and the valleys) were conquered from the sea, and the direction was from the lowest point upwards. This explains the name of the river Vinstra (The Left River), after which the Vinstradalen in Oppdal municipality is named. When you walk up the valley, you have the river on your left side, plain and simple as that.

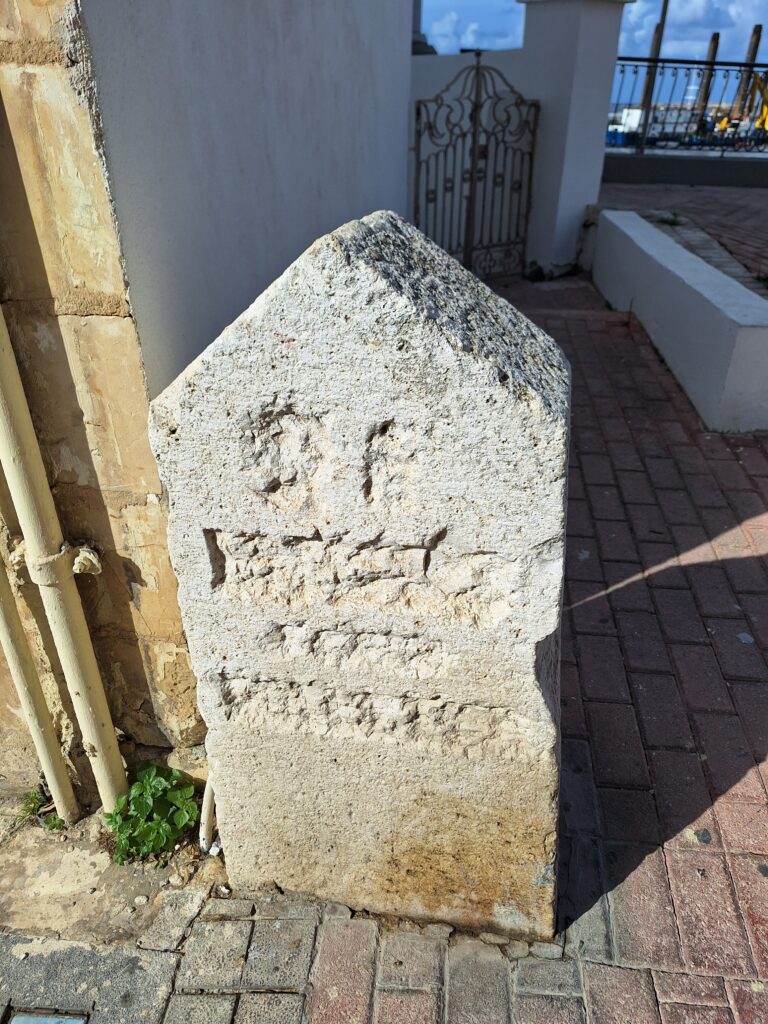

Vinstradalen runs southwards from Drivdalen, south of Oppdal center. Standing at the bottom of the valley looking north, you will be able to see the farm ‘Lo’ (meaning lowland fields close to water and forests) on the right side of Drivdalen, where king Håkon Håkonsson built a church and a royal farm around 1250. Nearby is also the farm ‘Rise’ (meaning bushland), where a number of archaeological finds have been made. It is assumed that the permanent settlement in Drivdalen has lasted 2000 years. The large burial ground at Rise (some of the tombs date from the 3rd century A.D.) was located by a track, as was the custom at the time. A bronze angel has been found here, which may have been attached to a reliquary shrine. This figure represents the archangel St. Michael, and was probably made in Ireland in the 6th-7th centuries. A wooden version is to be found in St. Michael’s Chapel in Vinstradalen.

Vinstradalen is lush, and the soil is rich in nutrients. There are several summer farms in the valley. When you park your car at the Trengen farm, you quickly see that sheep are a source of income here, with sheep sorting facilities (in Icelandic called ‘réttir’), and a cattle grid. But one can wonder how stupid the sheep really are, when you see this one:

The summer road up Vinstradalen is an excellent skiing track during winter, which can certainly be recommended (even if we didn’t have skis with us this time). However, at Easter 2024 the snow was hard and quite fine for shoes as well

A short kilometer into the valley you will find St. Mikael’s Chapel, named after the ‘Rise Angel’. The chapel was inaugurated in 2012 as part of the ‘Pilgrimsleden’. The road through Vinstradalen is one of three old traffic routes northwards from Oslo.

St. Michael’s Chapel is a gem, built like an amphitheatre, with the Oppdal nature itself as an altarpiece. It was designed by Yngvild Norigard from Drivdalen. Awesome!

… and if you need some extra help from above, there is a charming Jesus figure in the chapel as well.

We had read in the newspaper ‘Opp‘ about some ladies taking winter baths in Vinstradalen, and our aim for this trip was to find the waterfall where they had their Christmas bath. In the article, the walk from Trengen is described as ‘long and steep’, and we must say that it was quite a good description. Especially the word ‘steep’! Starting from the chapel, we slid down on last year’s half-rotten birch leaves. It was so steep that Idun occasionally sat on her bum and let the back of her trousers take the brunt.

Despite all difficulties (or maybe even because of?) it turned out to be a really nice visit. Vinstradalen is a canyon, i.e. a steep valley dug out of the river. Here (in the summer, if you’re lucky) you can enjoy the sight of the endangered species Black Curlew (don’t pick it!). In winter, there are other beautiful phenomena to see – made of ice. The sides of the canyon were decorated with an impressive amount of icy waterfalls – both impressive and beautiful!

We’re guessing that these are tiny streams in the summer, not sure if you even notice them at all. But in the winter, when the ice builds up, it’s a magnificent sight!

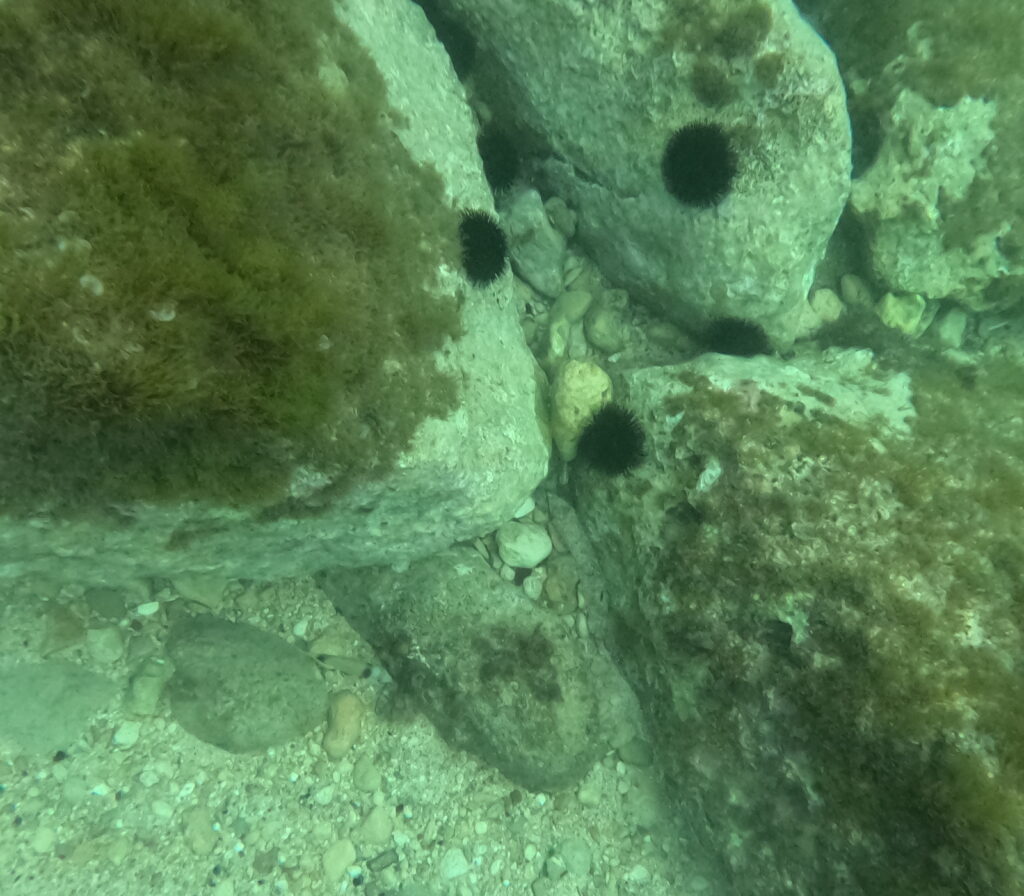

Once at the bottom of the valley, we wondered whether we should go up or down to find the bathing pool, but as the valley seemed to be more steep upwards, the choice fell to the right, and it was indeed the correct idea. A bath in Vinstradalen is just right!

Ref: Drivdalen.no