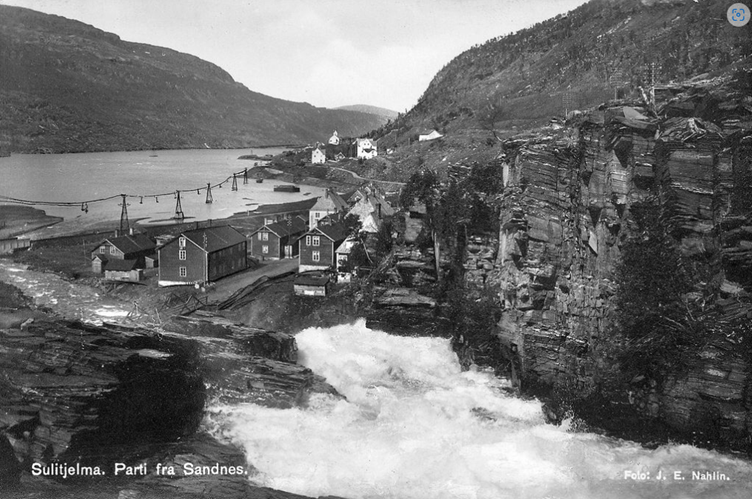

Port-en-Bessin-Huppain is a commune in Calvados, Normandy. Here, people have lived since the Bronze Age. The town of Port-en-Bessin was founded by Vikings, and it’s destiny has always been linked to the sea, which is also evident from the motto ‘Res Nostra Mare‘ = The sea is our law. It is situated in a small valley (fault) between high cliffs, about 10 km from Bayeux.

In 1972 it merged with the neighboring village of Huppain (from Norwegian/Norse: Oppheim). After 1096, Port-en-Bessin was called ‘Port des Évêques de Bayeux‘ (The ‘Bishop’s Harbour in Bayeux), and it was Bishop Louis de Harcourt who initiated the excavation of a deeper harbor basin in 1475.

This first, outer, harbor was destroyed in a storm in 1622, and that led to recession in the area. It wasn’t until 1866 that the harbor was fully reconstructed, and in the 1870’s and 80’s, first a smaller and later a larger inner basin were excavated.

Port-en-Bessin has always been connected to the sea and fisheries, but during the Allied landings in 1944, the village took on a very special role. To keep the war machine going, there was a great need for fuel. At the start of ‘Operation Overlord‘, this was solved in the somewhat cumbersome way: Transport by the use of cans. However, two offshore oil terminals were built in a hurry, and one (outside Sainte-Honorine-des Pertes) was connected to Port-en-Bessin with a pipeline. This was a very successful project, and already from June 14th, 100 tonnes of fuel passed through this small town every day.

The memorial stands by the outer harbour, and then a bath would be just right, wouldn’t it? We walked down to the beach just below the 1694 Vauban Tower, which was built to prevent English invasion. There used to be a similar tower on the hill above, but this was bombed by the Allies 6-8. June 1944, at the start of the landing.

The beach below the tower turned out to be a bit special. As a memorial to the local tradition of scallop fishing, you can wade in layers upon layers of shells. They seem to have dumped scallops here for decades!

However, the shells were well-rounded and not at all painful to step on – may we call them ‘Pebble scallops‘?

Anyway, then it was just a matter of jumping into the sea? Well… Yes, the sea was fresh and nice – a little way out. But we experienced quite a lot of wind this day, and large swells, which swirled up sand, hence brown water close to the land. And also quite a lot of seaweed to step over, which we normally wouldn’t give a thought. However, as you wade outwards, the sand is very quickly replaced by big stones (which explains the piles of seaweed on the beach), and combined with the waves, the bath turned out to be a little bloody. But apart from that – a nice bath by a very cozy little town.

And after the bath? If you are interested in scrap from World War 2, don’t miss ‘Le Musée des épaves sous-marines du débarquement‘ (D-Day Underwater Wreck Museum), which exhibits all kinds of artefacts and vehicles found on the seabed after D-Day. However, we missed this museum, and we would therefore instead recommend a trip to the episcopal city of Bayeux. There you can (and should!) visit ‘Le Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux‘, to see the Bayeux Tapestry.

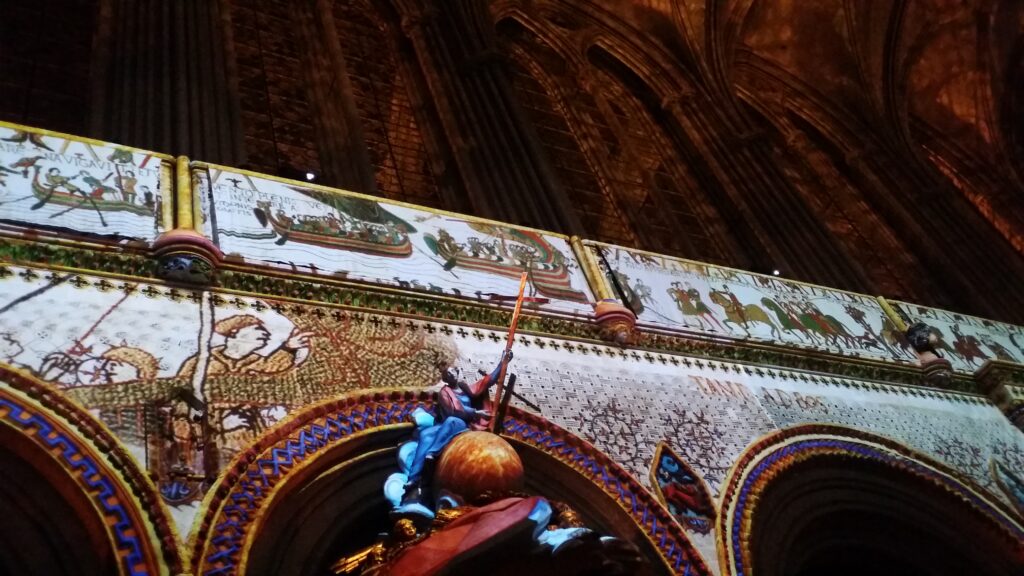

The carpet depicts King William the Conqueror’s invasion of England, as well as the Battle of Hastings in 1066 in 72 detailed scenes. Queen Mathilde’s role in the production has been very much debated, but anyway, the tapestry is absolutely marvellous, and the audio guide is also very good. Quote Audioguide: ‘They are approaching land. Everyone is happy. Even the horses are happy!‘. Here, retailers can really dive deep into the fashion, weapons, equipment and horse’s mood of that time.

The tapestry is 70 (!) meters long and 0.5 meters high. That was a very strange size, you might think. But this is carefully planned – to fit under the triforium in the huge nave of the Bayeux Cathedral. In this way, everyone could ‘read’ the cartoon about William’s exploits: Beating two armies, and thus conquering an entire kingdom, England.

A cathedral visit in France is always just right!