Egilsstaðir, with almost 3,000 inhabitants, is a natural starting point for several spectacular hiking and swimming experiences in the north-east of Iceland.

One of the biggest ‘wow factors’ you can get is Stuðlagil. You drive through a long, gravelly valley, Jökulsdalur. This is a wasteland with a few farms and some sheep.

It takes an hour to walk up to the gorge, a nice hike with a pedagocically well placed waterfall, Stuðlafoss, to enjoy about mid-way. Well, that’s if you keep to the east side of the river.

Alternatively, you can drive up to a stair access (239 steps) on the west side of Jökulsá, but we would not recommend that if you are fit enough for the east side, because:

- From the vantage point on the west side, you cannot see the most beautiful basalt columns.

- You can’t go down to the water.

After the waterfall, basalt columns begin to appear by Jökulsá. The river is (large parts of the year) bright green! Here we are talking about glacial rivers with lots of particles in the water. The basalt columns are first brown, gradually gray. Most of them stand vertically, but in some places a bunch of them are twisted around and you can see the cross section of them instead.

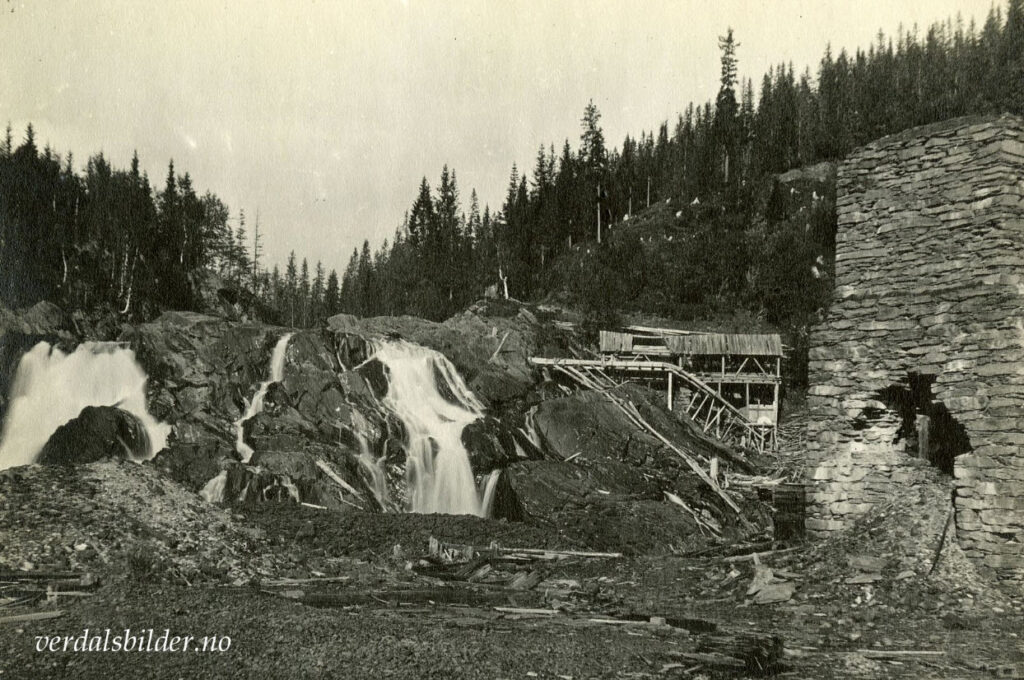

Stuðlagil is one of the newest tourist attractions in Iceland. The gorge came to light when the water level in the river Jökulsá á Brú was lowered following the very controversial construction of the Kárahnjúkavirkjun hydroelectric plant in 2009. The plant was supposed to ensure power supply to the aluminum plant in Reyðarfjörður.

Stuðlagil itself is like a cathedral with tall, beautiful columns. A wonder of Mother Nature! If you are careful, you can climb down to the river bank and sit on the basalt columns and just enjoy. We didn’t dare to do this on our first visit, it was in March; snow and ice everywhere. The second visit, however!

Stuðlagil is an absolutely magical place. However, be aware that the water level may rise if they let more water through from the power plant further up the valley. Because of this – and strong currents – we do not recommend swimming in Stuðlagil!

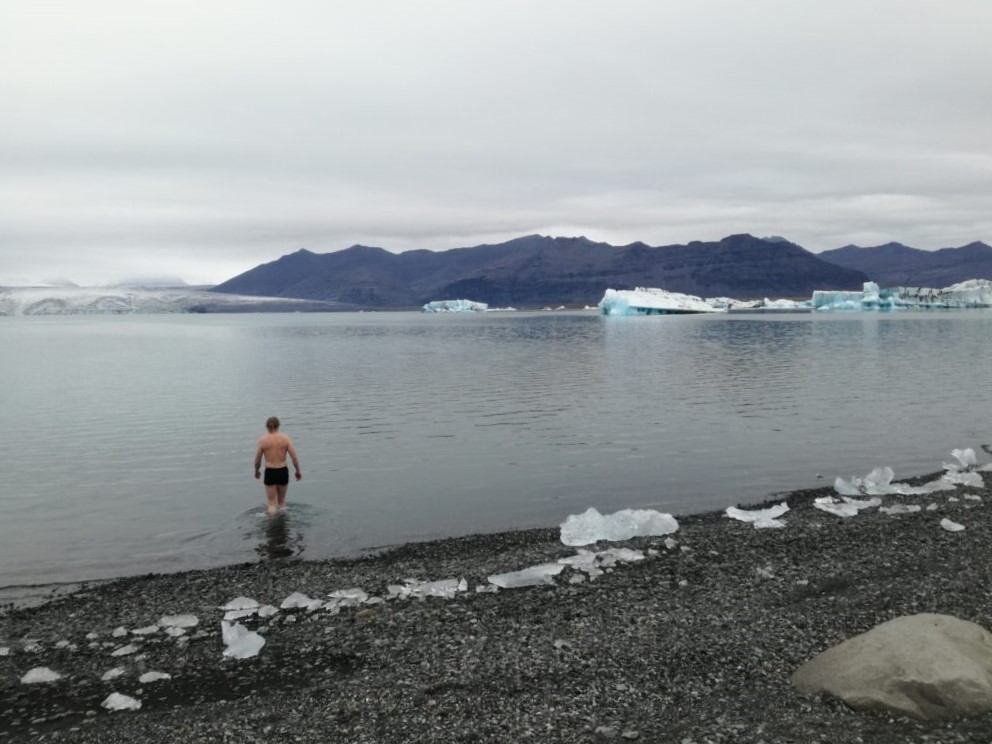

We (as you might have guessed) couldn’t resist in the long run. But we think we did a thorough risk assessment, had secured ourselves with a tow rope and only swam in a backwater without current. But this is not the place to try ice bathing for the first time!

After the ravine visit, a bath is just right. At Egilsstaðir there are two obvious options for open-air swimming: the river Lagarfljót and Urriðavatn lake. Lagarfljót basically looked a bit dirty and unappealing. The sad white-grey color comes from the particles in the water. Urriðavatn, on the other hand, is fresh and blue and cold – except it’s hot spring interior. But that’s another story – Vök Bad.

Of lengi í örbirgð stóð

einangruð, stjórnlaus þjóð,

kúguð og köld.

Einokun opni hramm.

Iðnaður, verslun fram!

Fram! Temdu fossins gamm,

framfara öld.

(E. Benediktsson, made for the opening of the power plant)

Too long left in destitution,

isolated, stubborn nation,

downthrodden, cold.

Monopoly opens the door,

Industry, save the poor!

Forward! Waterfall pour,

till time grows old!”

(E. Benediktsson, translated by Tobatheornottobathe, with some help from Google Translate)