Why do you have to take a several-day safety course to work offshore? Where does that idea come from? Most people probably don’t think much about this, but when it’s your turn to join a course, that’s when you start wondering.

When drilling off the coast of Norway started in the 1960’s, it was with completely blank sheets. We had many mines in Norway, and we were big in shipping, but no expertise in drilling and producing oil and gas at sea. It was necessary to lean on American companies, which had both expertise and capital. The first drilling on the Norwegian shelf was done by Esso in 1966, they had experience from offshore fields, including in the Gulf of Mexico. In the 1950’s, the personnel were transported out to the rigs by boat – a method that had its drawbacks. One thing was the use of time. The most important argument against was seasickness. There was a risk that the workers were ill and in bad shape when they started work offshore. The very first helicopter to be certified for civil aviation was the Bell 47B in 1946. Throughout the 1950’s, helicopter types with room for more passengers appeared, and it was decided from the beginning to use helicopters for all passenger transport to and from the Norwegian continental shelf. The authorities wanted a Norwegian supplier to handle the helicopter traffic, and the contract went to Helikopter Service A/S. Two Sikorsky S-61 machines were purchased, they made four trips per week. With this activity, the income was far from sufficient, and Esso sponsored Helikopter Service A/S with approximately 60,000 dollars per month at the beginning. It was Phillips who found the first viable (huge) oil discovery ‘Ekofisk‘ on Christmas Eve 1969. The first decades were characterized by a certain ‘Cowboy mentality’. The focus was on efficiency and production, unions were banned, and safety was often so-so. Rescue suits, for example, were not used.

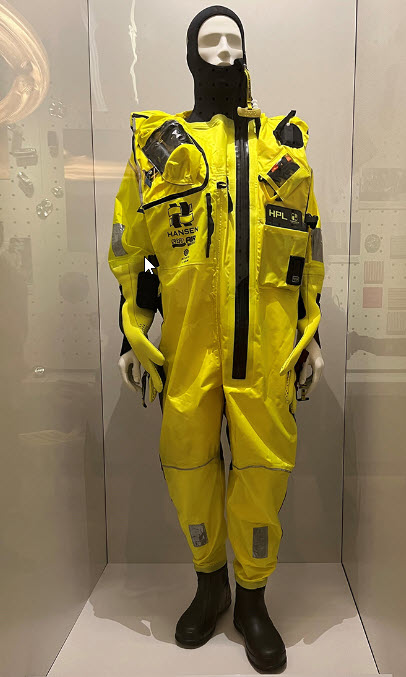

It soon proved impossible for the authorities to have control over everything that happened in the petroleum industry. The development sometimes went so quickly that the regulations were constantly lagging behind, and control offshore was difficult and time-consuming in terms of logistics. The development of safety systems was pushed forward by accidents. If you look at Ekofisk, this development alone resulted in 45 deaths, of which 1/3 were linked to helicopter accidents. The head of the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate’s security department, Arne Flikke, resigned in the summer of 1974 due to a lack of resources to exercise control. The solution was internal control. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate was supposed to check that the systems were in order, but they were not supposed to go into detailed checks on each individual installation. The companies that did not put in place a functioning internal control risked being ‘punished’ at the next license award. In 1978 there was an investigation (the Leiro committee) which recommended a 3-week safety course for offshore employees. However, this had not been implemented when Aleksander Kielland tipped on the 27th of March 1980. In this disaster, 123 people died. Of the 212 on board, only 76 persons had undergone safety training. The safety courses are therefore a consequence of the Aleksander Kielland accident. Rescue suits were not required by the offshore contractor companies, and almost everyone who died in the Kielland accident were employed by contractors. Therefore, the Norwegian Maritime Directorate decided in the autumn of 1980 that all offshore employees should be equipped with rescue suits.

The most important functions of the suit are insulation (retaining heat) and buoyancy. When evacuating in water, the use of a rescue suit will increase the probability of survival considerably.

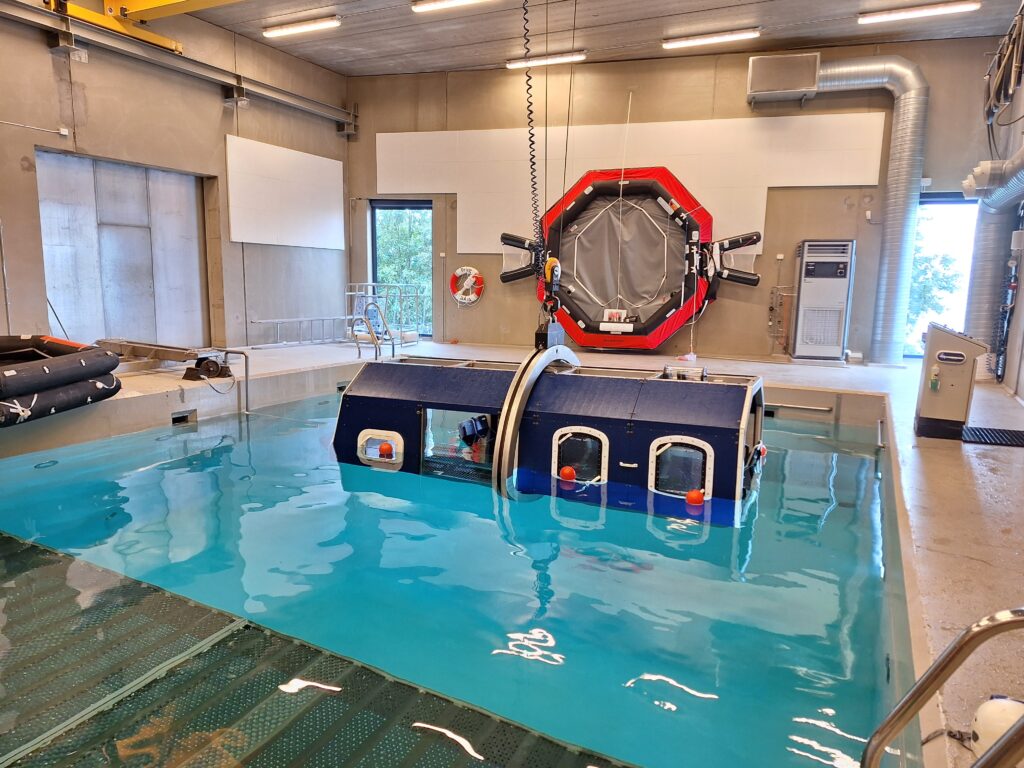

An offshore security course (2024) consists of a 4-day basic course, which must be refreshed with a 2-day repetition course every 4 years. One of the main elements is training in the use of rescue suits including breathing lung and helicopter underwater evacuation (HUET). The breathing lung is a waterproof bag that is mounted in the collar of the suit. A hose, valve and a nozzle are fitted to the bag. In an emergency situation, air is blown into the bag and the valve is closed before coming into contact with water. Then you have some air to breathe in until you get up to the water surface. The rescue suit has a lot of buoyancy, so when you first get out of the helicopter, you don’t need to swim to reach the surface. Having said that, this course, or a rescue suit for that matter, will not help the slightest if the gearbox breaks (as in the Turøy 2016 accident).

Before you get as far as the helicopter, you have to go through a number of introductory exercises to get used to the breathing lung. Idun was so out of practice that she breathed into the hose without closing the valve first (while we were still on land checking the equipment). It was 3 years since the last offshore trip and 4 years since the last course. Repetition is indeed necessary! The exercises in water went better. First, we had to lay face down in the water and breath into the lungs for 20-50 seconds. Then pull ourself along the edge of the pool by a rope, lying face down. The last exercise before the helicopter was to hang upside down on the edge of the pool, with your foot around the pool ladder and your head down. Not at all complicated for someone who likes to swim. If you are unfamiliar with water, the situation is of course completely different.

The heart rate rises considerably entering the helicopter. During the helicopter exercises, everyone has an instructor who only looks after you. Fastening the seat belt (4-point) properly is practiced, which is the first thing to do if you hear the pilot say: ‘Brace, brace‘. There are various stories about things that have gone wrong on the courses, and a classic failure is turning the seat belt knot inwards. The opening mechanism is easy to trigger, but a colleague of Idun had once turned it so that it faced his stomach, with consequent stress, he lost his grip on his reference point (the window), and ended up on the roof (floor) of the helicopter when it turned upside down under water. Then it’s ok to have instructor help!

The instructor’s inquisitive look at Idun turned to laughter when she realized that ‘Wow, you actually like this!‘ After 4 evacuations from helicopter under water, the conclusion is that it’s quite fun when ‘Toworkornottowork‘ turns into ‘Tobatheornottobathe‘!

Ref:

https://www.aftenbladet.no/

https://www.norskolje.museum.no/

Tore Jørgen Hanisch og Gunnar Nerheim: Norsk Oljehistorie, ISBN 82-7443-018-2

Store Norske Leksikon

Wikipedia