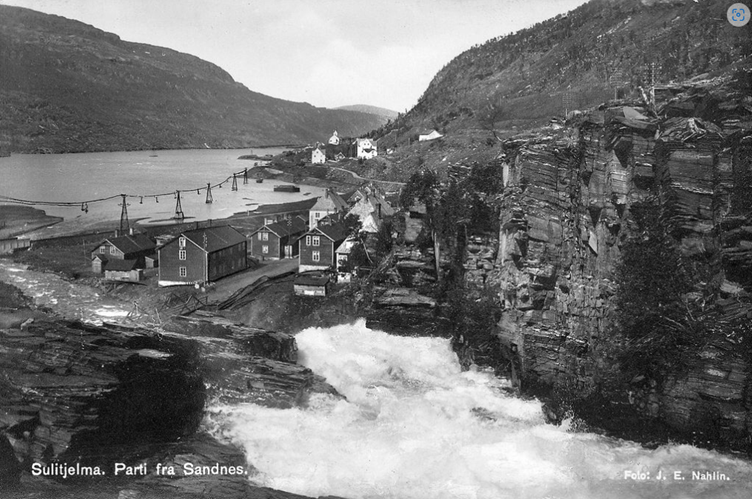

The Swede Nils Persson founded Sulitjelma Aktiebolag 10/2-1891, after 4 years of trial operations. Sulitjelma had a permanent settlement of 50 in 1880, which increased to almost 3,000 within 30 years. The immigrants came from all over the northern hemisphere, and the community became a conglomerate of Sami, Kven, Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, Germans and Russians. Here you could make money, but the work was hard and the living conditions miserable, especially in the early days.

Sulitjelma’s nickname for many years was ‘The Hell of Lapland‘, which says something about the poor conditions. The term was first used by the agitator Kata Dalström, the writer August Strindberg’s niece. It was strictly forbidden to agitate for trade unions. All agitators were chased from the village as soon as they were discovered. As was said in Sulis: ‘Norway’s laws stop at Finneid‘. A female agitator who managed to speak in the Sulitjelma mines before the spies discovered her, was Helene Ugland from Froland near Arendal:

“Aren’t you worth as much as the foremen and leaders? No, you are worth more. Do you understand that? It is you and your dirty, powerful fists that have value to the exploiters. You are the ones who raise money for the foremen, the managers, the clerks or whatever they are called, the ones who squander it. And what do you get in return? Pay for the work… yes, but you get something else, too. You get mocked and fired if the managers don’t like you.“

Like many other mining communities, there was a clear distinction of class in Sulis. Clerks and engineers had good living conditions, high wages and access to hunting and fishing. Workers who tried to do some hunting, however, were dismissed. In the beginning, only the mining company had a shop (sometimes very poor products), so they got the money back from the workers. For a long time they also had their own money system in Sulitjelma. Hence, the Company could save all salaries in the bank, and earn interest on it.

A strategic ploy to keep wages down was to sell work assignments at auction once a month, a kind of auction called ‘lisitation‘. To get the job, the worker teams had to underbid each other, and the result was mistrust between the teams. The ‘Mining Act‘ of 1848 gave the mining companies the burden of support for the personnel when they had lived on the mine’s premises for two consecutive years. According to the law, sick or injured workers were therefore supposed to receive support from the Company, but this could be avoided by dismissing workers after 23 months of service at the latest. In this way, the Company could evict workers who were injured or fired, and also the families of workers who died. Later, the same (living) worker could easily get a new job – at Sulitjelma Gruber. Martin Tranmæl has said that Sulitjelma was “a small tsardom, where the capitalists ruled unrestrained“.

Towards the end of 1906, the management got an idea to introduce use of something they called ‘control marks‘. The point was to know exactly how many hours the individual miner worked. This was to happen by each worker being handed a lead chip in the morning. The chip was ment to be worn at the chest, and when the mark was returned at the end of the day, the working hours were clear. The chips were immediately named the ‘Sulis Medal‘, or the ‘Slave Mark‘, and were deeply hated. The scheme with the control marks was first introduced in the Charlotta mine, which the management knew had the largest proportion of workers with family responsibilities. It was thought that this would go under the radar in the other mines , but that did not happen.

At the Hanken and Charlotta mines, 200 men were dismissed when they refused to wear control marks, and a rebellion, the ‘Mark War‘, spread from mine to mine. The workers wanted to start a trade union, but how was that to happen when the Company had banned all kinds of meeting activities? The Company owned all houses, roads and all the land in the valley. They also had a private police force. Where could they meet? The solution was lake ‘Langvatnet’. Nobody owns the water, and the 13th of January 1907; 1,300 people met on the ice at Langvatnet. Ole Kristoffer Sundt spoke standing on a margarine box: ‘Everyone who wants to join the trade union goes to the left!‘ No one stepped to the right. This happened during church time, and the comment from the priest was as follows: ‘The old Sulitjelma is falling now!‘

After the meeting at Langvatnet, 13 trade unions were established: 7 for miners and 6 workers’ unions. Sulitjelma had scattered settlements and difficult transport conditions, therefore this many departments.

After living with the Sulis movie for many weeks in 2022, Tobatheornottobathe just had to take the trip to Sulitjelma and experience the place for ourselves. We wanted to have a bath in lake Langvatnet! Ideally it should have been done through a hole in the ice, but as the premiere was set to October, this was relatively impossible. And where to swim? Langvatnet (Spoiler alert!) is actually quite long, almost 11 km (under a kilometer wide), so the possibilities are many. We chose the new housing estate Charlotta, built on the slag heap of the Charlotta mine.

A bath here was fine for us, but as previously mentioned: The locals hesitate, because of polluted water!

Ref:

– Frifagbevelse.no – https://frifagbevegelse.no/magasinet-for-fagorganiserte/slavemerket-som-reiste-arbeiderkampen-pa-norges-nest-storste-arbeidsplass-6.469.821411.e4bf5b2fa7

– Eyvind Viken: ‘Pioner og agitator – et portrett av Helene Ugland‘, Falken Forlag, 1991

– Wikipedia: Sulitjelma Gruber